Throughout

history, cases of man's inhumanity to his fellow man abound. The

German Holocaust is known and condemned by all. Public outcry is

long and loud over newer

instances such as the

Bosnian genocide.

The United States is not free from guilt. The tragedy of "The Trail

of Tears" cries for remembrance throughout the ages. Although not as

well publicized as some other instances of genocide, the Cherokee

Removal was American history's ultimate betrayal.

|

Marker commemorating those who died

on the

Trail of Tears |

Before it ended, 4,000 Cherokee lay dead. An entire nation was

dispersed never to be reunited again. One national American hero's

feet of clay were forever exposed and political hypocrisy and deceit

reached an all time high. The tiny site of New Echota near

Cartersville was the hub of it all. The Georgia State park situated

there today recreates the old Cherokee capital. The park musuem is

the perfect place to begin your tour of the Cherokee Trail in

Georgia.

In 1825,

New Echota was the heart and soul of the Cherokee Nation. By 1835, it was ghost

town. Fate and history linked all the actors in this tragic drama

before the final curtain fell on the Cherokee hopes and dreams and

arose on the opening of a new frontier for the white settlers.

was the heart and soul of the Cherokee Nation. By 1835, it was ghost

town. Fate and history linked all the actors in this tragic drama

before the final curtain fell on the Cherokee hopes and dreams and

arose on the opening of a new frontier for the white settlers.

|

| Council

House at New Echota |

The villain of the piece seems clear.

Andrew Jackson , hero of the battle of New Orleans, long time Indian fighter and

finally president of the United States.

The hero is harder to see. Was it

John Ross

, hero of the battle of New Orleans, long time Indian fighter and

finally president of the United States.

The hero is harder to see. Was it

John Ross ,

Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation? Was it

Sequoyah

,

Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation? Was it

Sequoyah , the man who overnight made his people literate? Where does history

place

Elias Boudinot

, the man who overnight made his people literate? Where does history

place

Elias Boudinot ?

He edited the first Cherokee newspaper, The Phoenix. In just four

short years, his beliefs did a complete about face. Then there was

Major Ridge

?

He edited the first Cherokee newspaper, The Phoenix. In just four

short years, his beliefs did a complete about face. Then there was

Major Ridge ,

Chief of the Cherokee police, The Lighthorse Patrol, Counselor to

his good friend Chief John Ross and Speaker of the Council in the

Cherokee lower legislative house. And where did Elias' brother Stand

Watie fit in. When he helped the Georgia Militia destroy the Phoenix

printing press. Did he stomp the soft lead type into Georgia's red

clay in an effort to preserve the Cherokee heritage or to line his

pockets? What of the

supporting cast? History may have overlooked them but the drama of

the Trail of Tears would have been different were it not for their

contributions. Samuel Worcester and Junaluska‘s deeds are forever

interwoven in Georgia's history of this time.

,

Chief of the Cherokee police, The Lighthorse Patrol, Counselor to

his good friend Chief John Ross and Speaker of the Council in the

Cherokee lower legislative house. And where did Elias' brother Stand

Watie fit in. When he helped the Georgia Militia destroy the Phoenix

printing press. Did he stomp the soft lead type into Georgia's red

clay in an effort to preserve the Cherokee heritage or to line his

pockets? What of the

supporting cast? History may have overlooked them but the drama of

the Trail of Tears would have been different were it not for their

contributions. Samuel Worcester and Junaluska‘s deeds are forever

interwoven in Georgia's history of this time.

The drama had

its prelude when the first settlers, led by men like

Daniel Boone first looked upon the land of the Cherokee and coveted it for

themselves. The first act, bringing most of the main players

together began in the early 1800's.

first looked upon the land of the Cherokee and coveted it for

themselves. The first act, bringing most of the main players

together began in the early 1800's.

In 1814,

Jackson was ordered to stop the uprising of the Creek. The

culmination of the Creek War was the battle of Horseshoe Bend in

March of that year. Many of the Cherokee stood with him. Jackson

appointed Ridge "Major" .A title he would use as his name for the

remainder of his life. John Ross, Ridge's close friend, was a

lieutenant during that war. Sequoyah was another Cherokee who would

both fight under Jackson and also play a part in the drama that

would lead to The Trail of Tears. John Ross swam across the frigid

Tallapoosa River to steal the Cheek canoes, which were then used in

a diversionary, attract by the Cherokee. Ridge's canoe was the first

across the river on that fateful day.

Junaluska , another Cherokee warrior, is credited with saving Jackson's life

at that battle. Thus the Cherokee were shocked when after the war,

Jackson forced the Creek to sign over 22 million acres of land in

Southern Georgia and central Alabama of which a large part was

considered Cherokee land.

President James Madison sided with the Cherokee but just

months later, Jackson was successful in getting most of the land by

means of a treaty signed a group of chiefs, including Sequoyah, The

handwriting was on the wall. Whatever the Cherokee did to prove they

were loyal, law abiding people, however many times the courts upheld

their claim, their fate was sealed.

, another Cherokee warrior, is credited with saving Jackson's life

at that battle. Thus the Cherokee were shocked when after the war,

Jackson forced the Creek to sign over 22 million acres of land in

Southern Georgia and central Alabama of which a large part was

considered Cherokee land.

President James Madison sided with the Cherokee but just

months later, Jackson was successful in getting most of the land by

means of a treaty signed a group of chiefs, including Sequoyah, The

handwriting was on the wall. Whatever the Cherokee did to prove they

were loyal, law abiding people, however many times the courts upheld

their claim, their fate was sealed.

|

|

| The

enterior of the Cherokee Council House, similar to our

Senate. The portraits over the mantle are Chief George

Lowrey, Chief John Ross and Major Ridge |

The Cherokee

Supreme Court. The Cherokee had a form of government similar

to the U.S. |

In spite of

Jackson's treachery, Ridge and many of the Cherokee still supported

him throughout the Seminole War. In 1823 Jackson, who had earned his

nickname of "Old Hickory" for his toughness, was elected to the

Senate. He used this position as a stepping stone to the Presidency

in 1828. One of his first acts was the passing of the "Indian

Removal Act". Between 1814 and 1824, Jackson held a key role in

negotiating nine out of eleven treaties, which would force the

Native Americans off their ancestral land to less desirable land out

west.

Chief Junaluska

who had saved Jackson's life at Horseshoe Bend, went to plead with

Jackson for the protection of his people and was met with the reply:

"Sir, your audience is ended. There is nothing I can do for you".

Junaluska later

stated, "Oh my God, if I had known at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend

what I now know, American history would have been differently

written."

In 1819 the

Cherokee Council began holding their official meetings in Newtown, a

small community in Northwest Georgia. It was officially proclaimed

the Cherokee capital and its name changed to New Echota in 1825. By

1927, the Cherokee had established a form of government modeled

after the United States. They built civic building there to house

the seat of their government. By 1830, Cherokee surveyors had laid

out a well-planned community. It had a two-acre town square with a

60-foot wide main street. This was a small town of about fifty

permanent residents most of the year but when council meetings took

place, it was a buzzing hive of activity. Legislators arrived to

attend sessions in the upper or lower council house. Justices came

to sit in judgment in the city's Supreme Court Building. The poor

and the wealthy alike came to their capita city for a lawmaking

session and to enjoy a social get together. The indigent walked into

town. The wealthy Cherokees arrived in elegant carriages with their

elaborately gowned wives and daughters. Their sons rode besides them

on sleek horses. Their slaves attended to their needs much as the

denizens of Georgia's capital city, Milledgeville.

|

|

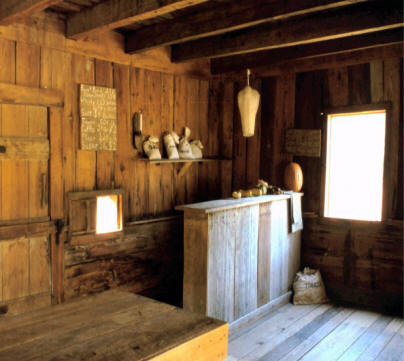

| Vann's Tavern at New Echota. This

is an original building that was moved to the state park. |

Vann's Tavern interior. In addition

to being planters,

the Vann's were sucessful business

men. |

One of the

wealthiest of the Cherokee was Rich Joe Vann. He lived in luxury on

his successful plantation built by his father, Chief James Vann. It

was the first brick house ever built by a Cherokee and shows a

marked Moravian influence in style and design. The centerpiece of

his home is the magnificent cantilevered staircase.

The doors, known as Christian doors, have features

representing a cross and an open Bible.

|

|

|

The Vann House

(Credit all Vann

House Pictures to Martin Walls |

Famed cantilevered staircase in

Vann House |

Objects excavatred at the Vann

House |

Chief Vann's house also included a blacksmith shop, the 800-acre property around

the Vann House with 42 slave cabins, 6 barns, 5 smokehouses, a

trading post, more than 1,000 peach trees, 147 apple trees, and a

still.

house also included a blacksmith shop, the 800-acre property around

the Vann House with 42 slave cabins, 6 barns, 5 smokehouses, a

trading post, more than 1,000 peach trees, 147 apple trees, and a

still.

After

constructing The Vann House, James lived at the house for 5 years

before he was killed at Buffington's Tavern in 1809. After his death

he left the house to his favorite child, Rich Joe, who occupied it

until the Removal. It is another "must visit" to understand the

Cherokee heritage in Georgia.

If the city of

New Echota represented the pride of the Cherokee Nation, its voice

was The Phoenix, their national newspaper. Housed in a modest frame

building, The Phoenix bound the far-flung tribe together. The

Cherokee were the only Native Americans to have their own written

language. A young Cherokee named Sequoyah devised a Cherokee

alphabet in 1821. He had worked on the concept for 12 years and

finally developed a syllabary, which allowed any Cherokee speaker to

become literate in two weeks. The concept was called the "Talking

Leaves" by the Indians as a slur on the white man's use of the

written word. The Cherokees felt the white man's written words were

like the leaves that dried up and blew away when the words were no

longer suited.

|

|

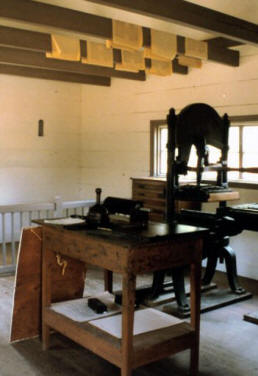

| Phoenix replica at New Echota |

Printing Press in Pheonix building |

This alphabet

led to the founding of the national paper in Feburary1828. Elias

Boudinot was a natural for the first editor. Born Gallegina (Buck)

Oowatie – the Oo was later dropped from the surname- he was educated

in Connecticut and traveled extensively throughout the east as a

young man. On his travels through Washington, young Buck met Dr.

Elias Boudinot, a statesman best known as having served a term as

President under the Articles of Confederation. A strong friendship

developed and Buck adopted the name of his mentor. As Elias

Boudinot, the young Cherokee was a staunch proponed of a national

paper and helped raise money for the project through speaking

engagements. Politically, at this time, he was a strong backer of

Chief John Ross's Nationalist Party. Elias and his new bride,

Harriet Gold of Connecticut, settled down in a small cabin just down

the street from the Phoenix office.

During his time

in Connecticut, Elias had developed a close friendship with Samuel

Worcester. Samuel was a seventh generation minister. He had a gift

for languages and knowledge of printing from his father who had

worked as a part time printer.

Elias asked Samuel to come to New Echota and help with the

development of the newspaper. Samuel and his wife also used their

mission connections to help fund The Phoenix. His Cherokee name, The

Messenger, reflects his great input into the paper until his death

in 1859 in the Oklahoma Territory.

Samuel and Ann's home was built near the outskirts of the

Cherokee capital and still stands today.

|

| Samuel Worchester's house. The only

building original to the site |

Another close

friend and cousin of Elias and his brother,

Stand Watie ,

was John Ridge, son of Major Ridge. Major Ridge came to see the West

as the only hope for his people to survive as a nation. Ironically,

both Elias and John Ridge supported the 1829 law that mandated the

death penalty for any Indian who signed away Cherokee land. However,

by 1832, Elias had converted to Major Ridge's Treaty Party that

advocated removal to Oklahoma. Even though the Supreme Court had

supported the Cherokees, President Jackson is reputed to have

stated, "John Marshall has made his decision. Now let him enforce

it." He probably was too clever a politician to have actually spoken

those words but they reflected his sentiments

and his actions accurately.

This is the same man who earlier promised John Ross that Cherokee

lands would be theirs "as long as the grass grows."

,

was John Ridge, son of Major Ridge. Major Ridge came to see the West

as the only hope for his people to survive as a nation. Ironically,

both Elias and John Ridge supported the 1829 law that mandated the

death penalty for any Indian who signed away Cherokee land. However,

by 1832, Elias had converted to Major Ridge's Treaty Party that

advocated removal to Oklahoma. Even though the Supreme Court had

supported the Cherokees, President Jackson is reputed to have

stated, "John Marshall has made his decision. Now let him enforce

it." He probably was too clever a politician to have actually spoken

those words but they reflected his sentiments

and his actions accurately.

This is the same man who earlier promised John Ross that Cherokee

lands would be theirs "as long as the grass grows."

The Georgia

Militia was becoming ever more violent in its control of the

Cherokee. Federal troops had been removed and Georgia Governor

George Gilmer had begun the "Land Lotteries" which dispensed the

Cherokee land to new White settlers. The discovery of Gold in nearby

Dahlonega sealed their fate. Civilization, literacy and justice

could not stand in the way of "gold fever'.

In an editorial, Elias stared the position of the Indians.

"Full license to out oppressors and every avenue of justice closed

to us. Yes, this is the bitter cup prepared for us all…. I am

induced to believe there is danger, ‘immediate and appalling,' and

it becomes the people of this country to weigh the matter rightly,

act wisely, not rashly, and choose a course that will come nearest

to benefiting the nation."

This was

written as he watched the forts constructed to house his people

beginning as early as 1830. In his mind, there was no good choice,

only the lesser of two evils. He believed the best choice available

was to sign the treaty required by the Supreme Court to transfer the

Cherokee lands and move peacefully west.

The persecution

also affected any whites who supported the Indians. When the state

of Georgia began plans for the Land Lottery of 1832,

Samuel Worcester and eleven other ministers met in New Echota and signed a resolution

protesting the Georgia laws calling for any whites who worked on

Indian land to apply for a license from the State of Georgia. For

daring to defy the law, Governor Gilmer ordered him arrested by the

militia. Even as late as 1832 when the Supreme Court ruled that the

Cherokees were an independent nation and all disputes fell under

federal jurisdiction, the Governor refused to release Worcester and

the other clergymen. He was finally released by the next governor,

Lumpkin and moved to Oklahoma to prepare for the inevitable. .

and eleven other ministers met in New Echota and signed a resolution

protesting the Georgia laws calling for any whites who worked on

Indian land to apply for a license from the State of Georgia. For

daring to defy the law, Governor Gilmer ordered him arrested by the

militia. Even as late as 1832 when the Supreme Court ruled that the

Cherokees were an independent nation and all disputes fell under

federal jurisdiction, the Governor refused to release Worcester and

the other clergymen. He was finally released by the next governor,

Lumpkin and moved to Oklahoma to prepare for the inevitable. .

By 1832, Elias'

belief in removal as the only sensible choice forced John Ross to

remove him as editor. Ross believed that as long as the law of the

land supported their position, the Cherokee could maintain their

ancestral lands. Ross was an enigma. He was only one-eighth Cherokee

(technically his removal was illegal even by the federal standards

as the law called for removal of any person who was at least one

fourth Cherokee.) He

was the voice of the majority of the Cherokee from the time he was

elected principal chief in 1828 until his death in 1866 in the

Oklahoma Territory, yet Ross refused to speak Cherokee in the

council hall. He felt his command of the language was too weak. He

was one of the first Cherokees to advocate the sale of Indian land

when he supported the sale of a piece of property to the Morovian

Missionaries for a school. When Jackson sought the Cherokee land

after the Creek War, Ross was the principal negotiator sent to

Washington to fight the encroachment. When he returned, after having

to cede only a small portion of the land, the Council drew what they

believed the final battle lines. They passed a law making it

treason, punishable by death, to sell or cede Cherokee land. Until

1835, Ross used the weapons he understood best to protect his tribal

heritage; diplomacy and legal maneuvers.

John Ross

appointed his brother in law, Charles Hicks' editor but the paper

closed down due to lack of funds in May 1843. Fearing the militia,

Ross tried to remove the printing press to a safer location in

Tennessee. By this point the split between the two parties had

reached a point that Stand Watie, Elias' brother reported Ross'

intentions and actually joined the Georgia soldiers in destroying

the type and burning the building.

_800x533.JPG) |

| Major Ridge's protrait at

Chieftains Museum |

Major Ridge,

leader of the treaty party, was another important character in this

drama. His home, known as the Chieftains Museum, is well worth a

visit to help understand this complex and intelligent man.In the

past he had stood up for what he believed regardless of the

consequences. Prior to the Creek War, he faced down another chief

who called for war with the whites. He and two other chiefs, James

Vann and Charles Hicks, executed an older chief, Doublehead, for

selling tribal land to the whites. He organized the Cherokee

warriors to fight with Jackson against the Creeks. After the war,

Ridge returned to devote himself to politics and his family

businesses, which included farmland, orchards and a store. Like John

Ross, Ridge was a wealthy man. He was a Speaker of the Council and

became an advisor to John Ross when he was elected chief. In

December of 1835, Ridge, his son, John, Elias Boudinot, Stand Watie

and twenty other men gather at Elias' home in New Echota. They

signed the Treat of New Echota. The following day about 200 members

of the Treaty Party ratified the treaty. Jackson had what he needed

to "legally" remove the Cherokee. The signers received money and

choice land in Oklahoma but did Ridge and his followers sign the

infamous treaty for the money or in the hope of a future for the

Cherokees? At least in Ridge's case, the statement he made after

signing makes his motives clear.

He laid down the pen and stated, " I have just signed my

death warrant."

Ross hurriedly

gathered 16,000 signatures of Cherokees stating the treaty was not

the will of the Cherokee People. Jackson pushed the treaty through

the Senate with just a one-vote margin. Within three years New

Echota was a ghost town. Some of its residents left voluntarily to

go out west. Ridge, John, Elias and Stand Watie all moved to the new

homeland but within six months, three of the four principals of the

treaty lay dead. Brutally killed by some of the tribal leaders who

saw their actions as treason. Of the four only Stand Waite escaped

and lived to fight again. Ironically, he later became the

highest-ranking Indian officer in the Confederate Army, Brigadier

General. He was the last confederate officer to surrender, holding

out for two months after Lee surrendered.

About 13,000 or

so Cherokee were left when the soldiers arrived to herd them to the

forts prior to the march, Over 4,000 men women and children died

before the Cherokee reached their barren new home. A few hundred

managed to evade the Georgia Militia and remained hiding in the

woods. These few comprise the ancestors of the Eastern Band of

Cherokees living in North Carolina today.

_800x533.JPG) |

| Chieftains Museum in Rome Georgia |

Beneath the red

clay of New Echota, the remains of the Cherokee printing type lay

buried like their dreams of peaceful coexistence or perhaps a state

of Cherokee. A few white people tried to occupy the houses that

remained but perhaps they felt uneasy. Many felt spirits lurked in

this place of death.

Most of the buildings at New Echota slowly crumbled into ruins. For

over a century, the capital city slowly surrendered to the tangles

briers and underbrush that encroached on the abandoned site. It was

the abode of birds, deer and other forest creatures.

In 1954,

archeologists, working with the Georgia Historic Commission and the

National Park Service began to excavate the site. When one excavator

found a tiny piece of lead, the workers made a circle around the

spot and within two days, 1700 pieces of type had been unearthed.

800 of the pieces could be identified as Cherokee symbols. The rest

was too badly damaged to be decipherable.

When the State

of Georgia opened the site as a park in 1962, Samuel Worcester's

house was the only original building left intact. A tavern once

owned by James Vann was moved to the site. The stare reconstructed a

replica of the Phoenix office complete with a similar press. About

600 pieces of the original type are displayed there and a copy of

the first issue of the Phoenix. The Supreme Court, the council

building and many dwellings have also been recreated.

The only thing that can never be returned to the site is the

hope of a nation before their neighbors sent them on the

"Nunna daul Tsuny", "The Trail Where They Cried."

For more

Info:

http://gastateparks.org/NewEchota/

http://gastateparks.org/ChiefVannHouse

http://chieftainsmuseum.org/

www.americanroads.net

American Roads

Promote Your Page Too