Fayette

Historical State Park and Townsite

Story

and Photographs by Tom Straka

Michigan’s Upper Peninsula has lots of fascinating towns and

museums to visit. Many of the museums are related to the

region’s pioneering industries: copper, iron, and timber. The

Upper Peninsula once had huge iron resources and over two-dozen

iron blast furnaces, and many of the museums and historical

attractions deal with the iron mining and smelting industries.

The fuel for nearly all of the iron smelting furnaces was

charcoal, and if you look hard you can even see some charcoal

kilns that still remain to celebrate the iron industry history.

Marquette was center of the iron activity and if you enter town

from the east, you’ll see a huge, reconstructed charcoal kiln

to welcome you to the city.

Charcoal kiln that welcomes visitors

to Marquette, prompting questions on its function, creating an

opportunity to explain the Upper Peninsula’s iron mining and

smelting history.

While the iron ore was near Lake Superior and Marquette, better

access to eastern smelters was available via Lake Michigan if

the ore could be moved south. In 1864 the Peninsula Railroad

was completed and provided that access. Ore could be moved

south from Negaunee (just south of Marquette where the mine

was) to Escanaba on Lake Michigan. The Jackson Iron Mining

Company in Negaunee began to transport iron ore to Escanaba in

1865 and from there to Cleveland, Ohio in a ship named Fayette

Brown, which could make the round-trip in just over eight days.

Shipping ore from Escanaba to foundries further east on the

Great Lakes was expensive, especially since the ore was 40

percent waste material. The answer to the problem was to build

a blast furnace to convert the ore into pig iron prior to

shipping to iron and steel plants on the Lower Great Lakes. The

furnace location needed to be close to Escanaba’s ore docks,

possess a natural harbor, and have access to local limestone

and hardwood forest resources.

In 1867 the Jackson Mining Company acquired 26,000 acres of

hardwood timberland east of Escanaba and that timber would be

converted into charcoal to fuel an iron furnace. The furnace

was built about 20 miles to the east (by water) of Escanaba at

a location named Fayette, constructed on a peninsula with a

natural harbor and limestone cliffs. Ore was shipped from

Negaunee to Escanaba, then loaded onto scows and towed to the

furnaces at Fayette where it was smelted into pig iron.

Charcoal kilns would be built at the furnace and in the nearby

forests. The location would become a townsite. The town became

an iron furnace company town, a community that supported the

smelter activity. It operated from 1867 to 1891 and produced

nearly a quarter-million tons of iron. A changing iron economy

and exhausted timber resources were the reasons for the furnace

abandonment.

Fayette hung on for a while after the furnace closed, but

eventually became a ghost town.

Later, it was recognized as one of the best-surviving former

iron furnace communities and acquired by the state to become a

historical park.

Today there are over 20 well-preserved buildings and structures

that present a picture of what the community looked like. The

second Saturday in August is Fayette Heritage Days with period

displays, food and music.

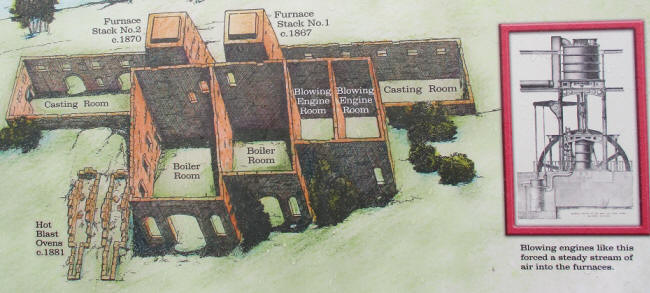

Since

Fayette

was an iron manufacturing community, the center of activity in

the town was the two large blast furnaces (or stacks), a

battery of charcoal kilns, a lime kiln, and a large dock. The

hot blast was provided by machinery housed on the upper level

of furnace complex. Steam was produced by boilers and sent to

blowing engines which provided the blast to the furnace. The

fuel was charcoal from the nearby hardwood forests and

limestone was quarried from the nearby bluffs. An

interpretative sign notes: “The furnace complex was the heart

of industrial Fayette. Here, the heat, roar, and odors of the

smelting operation merged with the shouts of men, whir of

engines and shill scream of steam whistles.”

The two blast furnaces and furnace complex, the productive heart of the community.

Inside one of the blast furnaces, where action took place.

The back of the stacks or blast furnace, elevated for access to

the stacks. These sections of the furnace complex housed the

machinery which powered the foundry’s hot blast. Boilers

supplied steam to the blowing engines which forced air through

the hot blast ovens and into the furnaces.

Illustration

of the furnace complex from interpretative sign.

Fuel was crucial to the operation. At first charcoal was

produced in rows of large rectangular charcoal kilns. The

rectangular kilns proved to be unsuccessful and were replaced

by more productive conical

charcoal kilns.

A row of ten conical kilns was next to the furnace; none

survive and a reconstructed kiln now represents that battery of

charcoal kilns. An interpretative sign next to the kiln states:

“Colliers manufactured charcoal to fuel the furnaces at a row

of kilns, like this reconstruction. The company also operated

kilns on the Garden Peninsula and contracted with private

operators to provide charcoal. By the mid-1880s, more than

eighty kilns were in operation within ten miles of Fayette.”

Shortages of fuel were always issues at the charcoal iron

furnaces. In 1870 the Escanaba Tribune reported: “Fears

were entertained that the supply of charcoal would fall short,

but with extraordinary exertions, they now have another set of

kilns ready, and the supply will be kept up.”

The reconstructed conical charcoal

kiln, imagine a row of them and the smoke they created.

A warehouse and general store was built in 1879. The store had

a captive market and did not always offer competitive prices. A

fire in the early 1900s destroyed the store and today only

stone walls remain. As to costs at the company store, one

shopper described the pricing policy as “pluck me.” The

interpretative sign at the machine shop states: “Machinists

like Louis Follo maintained Fayette’s industrial equipment from

this shop. Power machinery, used to manufacture equipment

parts, was driven by steam piped from the furnace boilers.

Master mechanics were paid $75 per month. Machinists like Follo

earned $1.80 per day.”

The skeleton of the company store complex.

The machine shop still survives.

A cluster of buildings remains and inside visitors can get a

glimpse of what life was like when Fayette boomed. An

interpretative sign states: “Fayette was a company town whose

residents depended on the Jackson Iron Company for jobs,

housing, medical care, and supplies. From 1867 to 1891 the

furnaces at Fayette produced high quality charcoal iron for

America’s steel industry and supported a bustling immigrant

community of nearly 500 residents. Today, twenty structures,

including the furnace complex, business district and employee’s

homes, recall the daily life of this industrial community.”

The

hotel is still in Fayette and the desk is ready for check-in. A

second-floor washroom featured a bathtub and sinks, with hot,

running water piped underground from the furnace complex. Hotel

guests used a two-story outhouse, accessed from the second

floor by a wooden walkway.

Typical middle class home at Fayette. Furniture would have been

shipped in from Escanaba.

Fayette Historic State Park is a must-see Upper Peninsula attraction. Its only a few miles off the main U.S. highway for travelers following the Lake Michigan coastline. The history of the region is tied to the iron industry, and this is the place to experience that history.

Author: Thomas J. Straka is a forestry professor emeritus at Clemson University in South Carolina. He is a regular contributor with an interest in history, natural exploration, and unusual sites.