Transformative Travel in Tulsa, Oklahoma

Story by Renée S. Gordon

Archaeological evidence exists attesting to the fact that

Native Americans inhabited the Oklahoma region as early as 500

AD. The state’s documented history begins with the Spanish

explorations of Francisco Vasquez de Coronado in 1541, followed

in 1682 by Robert de la Salle who claimed the land for France.

In 1803 Oklahoma was sold to the US in the Louisiana Purchase

and became part of the Arkansas Territory in 1819. On November

16, 1907 Oklahoma achieved statehood. The state’s story is a

microcosm of several pivotal aspects of untold American history

and proof that the truth is timeless.

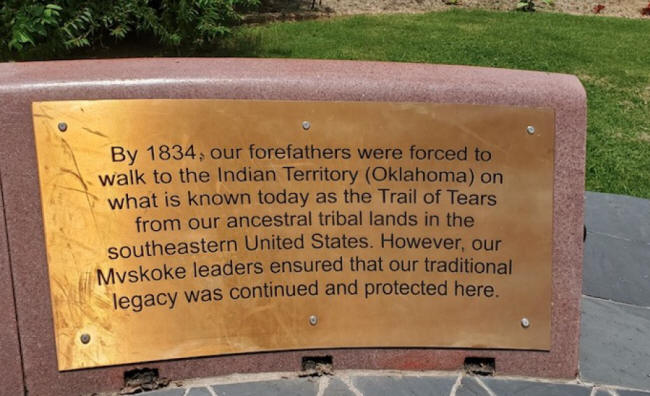

Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act in 1830 and from

1830-42 125,000 people, from five tribes, walked the Trail of

Tears from the South and Southeast United States to Indian

Territory. The Cherokee fought the act up to the Supreme Court,

where they won, but Jackson defied the ruling. The 1,200-mile

forced government migration allowed them to take only what they

could carry and it is estimated that as many as 15,000 people

died on the walk. The "Five Civilized Tribes" consisted of the

Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee and Seminole, many

holding slaves in bondage even after they reached Indian

Territory. Many fought on the Confederate side in the Civil

War.

Arriving in Tulsa they named it 'Tallasi', Creek for 'old

town'. The Creek Locapoga clan founded the first settlement in

Tulsa. Creek Nation Council Park indicates the site of their

new home. They placed ashes and coal from the fires of their

old home at the roots of a large tree, the Council Oak in 1836.

The park is designated on the National Register of Historic

Places.

Originally Tulsa was a cattle town with stockyards and shipping

facilities. Oil was discovered in 1901 and the city boomed.

Route 66, the first all-weather road, made the country

accessible from Chicago to Los Angeles in the 1930s. Known as

“The Mother Road,” it runs from east to west through Tulsa. The

76-ft. Golden Driller, the city’s iconic symbol is on view at

Expo Square. Weighing 43,500-lbs, it is stands near Route 66.

Arches at both ends mark the entrance and exit and there are a

number of markers and photo ops along the way.

Tally’s Good Food Café is an absolute must with a menu

consisting of more than 100 offerings and a décor that is

quintessential Route 66 chic. It has been the place to dine

since November 1987.

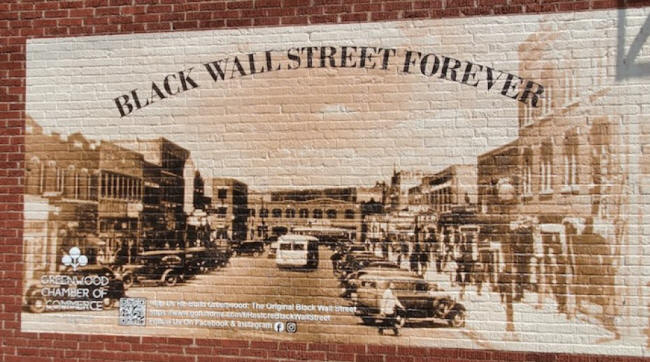

Several thousand African Americans, enslaved by the tribes,

traveled the Trail of Tears to Oklahoma and in 1866 government

treaties freed them and enumerated their rights. Many of them,

along with black settlers, established 50 African American

towns between 1865 and 1920. Only six of these towns remain.

Those who lived in larger cities created self-sustaining black

neighborhoods as a response to Jim Crow. Arguably the most

successful of these black districts was Greenwood, “The Black

Wall Street”, in Tulsa.

Greenwood was destroyed in what was originally known as the

Tulsa Race Riot because insurance companies did not have to

honor claims resulting from riots. In 2018 it was designated

the Tulsa Race Massacre. The event effectively caused the

residents to lose everything they owned and the ability to

create generational wealth, with no recourse for recovery. It

is believed 300 people died, 800 were wounded and $27-million

worth of property, approximately 35 blocks, was destroyed.

Much of the story has been shrouded in mystery but we do know

that on May 30, 1921 an African American worker, Dick Rowland,

needed to use the bathroom in the Drexel Building on Main

Street. An incident between 19-year old Rowland and Sarah Page,

a 17-year old, white elevator operator took place. She screamed

and he ran. The Tulsa Tribune headline, “Nab Negro for

Attacking Girl in Elevator”, fanned the flame. By that evening

there were calls for lynching the rapist and the sheriff found

it necessary to barricade Rowland, the deputies, and himself

inside the County Courthouse jail. A crowd gathered and white

men began looting resulting in the selection of 500 civilian

deputies after the Police Chief requested additional arms from

the National Guard Armory and was denied. Early the next

morning a request was made of the governor for the deployment

of the National Guard and martial law was declared. Black WWI

and other black male residents offered to protect Rowland but

were denied by the Police Chief. In the ensuing confusion a

white man attempted to disarm a black man and the gun went off.

That incident, along with numerous rumors of hundreds of blacks

on their way to invade Tulsa, was enough reason for whites to

march on Greenwood to loot and destroy. Six JN-4 biplanes took

to the skies and bombed the community.

On June 1, 1921 approximately 600 black residents were taken,

arms raised, to three internment camps. Blacks whites vouched

for were released; others were put to work, for wages, clearing

the rubble of Greenwood. Martial law ended on June 3rd, blame

for the “riot” was placed squarely on the armed black citizens

and the Police Chief was fired for failure to perform his duty.

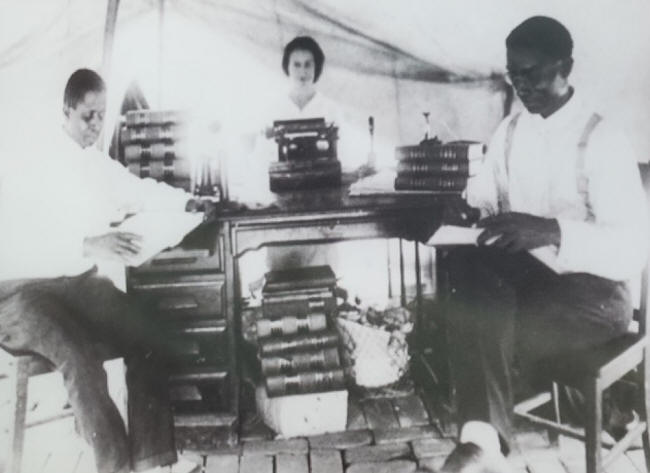

The Red Cross set up a service tent to aid in their first

non-natural disaster.

Brochures are available for a self-guided tour of the Historic

Greenwood District and related sites. The tour includes 16

stops that present a complete picture of the massacre through

locations, art, photographs and interpretive markers. The 100

N. block of Greenwood Avenue is the only remaining intact

block. Showcased on the street is a building with a façade made

of burnt bricks collected from the massacre and the nearby art

deco Oneok Stadium provides a view of the entire area from the

upper tier. The block is on the National Register of Historic

Places.

Greenwood Cultural Center, two blocks away, exhibits

memorabilia and photographs from the community, a large mural

in the parking lot and the 1996 monument dedicated to Black

Wall Street. The complex also includes the Mable B. Little

Heritage Museum House, the sole original home standing from the

1920s massacre. A poignant mural and the Vernon African

Methodist Episcopal Church are across the street. The original

church was constructed in 1905 and burned down to the basement

during the massacre.

Mount Zion Baptist Church was founded in 1909 and was completed

in May of 1921. Two months later it was destroyed after armed

black men inside refused to submit to the National Guard,

police, and the citizenry. During the massacre white people went

to the top of Standpipe and Sunset Hill and fired on the

Greenwood residents below. The resulting killings are

memorialized with a marker at the base of Standpipe Hill.

Attorney Buck Colbert Franklin was interned for a few days

after the massacre. Upon his release he operated from a tent as

the lawyer for the victims. When a newly passed fire law

prevented the Greenwood citizens from rebuilding he filed a

claim against the city and the mayor. He took the case to the

Oklahoma Supreme Court, eventually winning, opening a path for

Greenwood’s reconstruction. He was unsuccessful in getting

insurance companies to pay Greenwood’s claims. In 2010 his son,

noted historian and Civil Right’s leader, John Hope Franklin,

was honored with the opening of Dr. John Hope Franklin

Reconciliation Park.

The 3-acre park consists of a Healing Walkway, Hope Plaza and

Tower of Reconciliation. A 16-foot monument is situated at the

entrance. It features three bronze sculptures, Humiliation,

Hostility and Hope. Humility is depicted as a black man with

raised hands. Hostility is an armed white man. The Red Cross

Executive Director carrying a baby depicts Hope. The sculptures

are replications of 1921 photographs. The plaza’s central

feature is the 27-foot Tower of Reconciliation. The tower

showcases the history of African Americans from Africa to

current reconciliation. Interpretive plaques around the plaza

honor prominent historic individuals. @JohnHopeFranklinCenter

Woody Guthrie was born in 1912 and went on to become one of the

most influential musicians of all time. He sang about the

natural beauty of America and the need for constant vigilance

to maintain our democracy and ensure economic, human and legal

rights. He sang of harsh realities, hard work, and the necessity

of hope. The center preserves and shares his body of work and

his lasting legacy through listening stations, themed galleries

and interactive displays. A highlight of the center is a Dust

Bowl Experience that allows you to live through the coming of a

dust storm.

The Gilcrease Museum is currently closed for renovations but

online exhibits of the collections are available. The museum

has one of the most comprehensive Western American art

collections. There are artifacts, documents and artworks by 400

artists, representing colonial times to the present. Three of

the most significant documents are a 1520 Diego Columbus letter

asking that African slaves be allowed to replace Indians as

workers, Benjamin Franklin’s personal copy of the Declaration

of Independence and an authorized copy of the Emancipation

Proclamation. There are 23-acre thematic gardens.

@gilcreasemuseum

Philbrook Museum of Art is a cultural and historical facility

inside an Italian Renaissance villa. The museum’s collection

includes African, American, American Indian and European

artworks. Educational and social events are regularly

scheduled.

Leon Russell, a renowned Oklahoma musician, graces a wall in

Tulsa’s downtown. The mural, painted by the artist Jerks,

captures Russell’s aura.

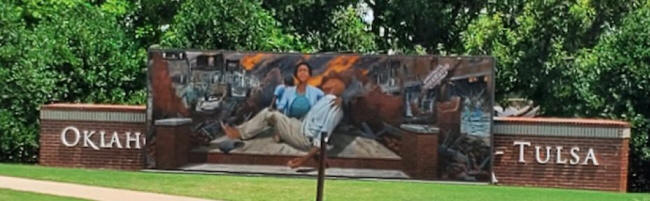

Tours of Tulsa begin with the airport artwork. “Signs of Life”

is a 13-ft. x 40-ft. collage mural by Liz Ingersoll and

dedicated in 2012. It depicts city landmarks that impacted on

the landscape and history.

Through the lens of travel our lives are transformed. We are

exposed to fresh ideas and new ways of viewing past events.

Tulsa is a good place to start. @visitTulsa