“Buffalo Soldiers In the Heart of America”

The Buffalo Soldiers National Museum in Houston, Texas

Renée S. Gordon

There have been no American military engagements in which

African Americans have not participated at some level. In the 1600s

British colonies blacks were used to defend against Indian

attacks. Massachusetts’ 1636 law was one of the earliest

documented laws to state that “all able-bodied Negroes” had to

report to serve in the militia. Enslaved and freedmen were

among the 9,000 African Americans serving in the Continental

Army as Patriots, largely in integrated units. During the War

of 1812 it is estimated that 15% of the soldiers and sailors

were of African descent and General Andrew Jackson called for

“free colored inhabitants of Louisiana” to enlist in the US

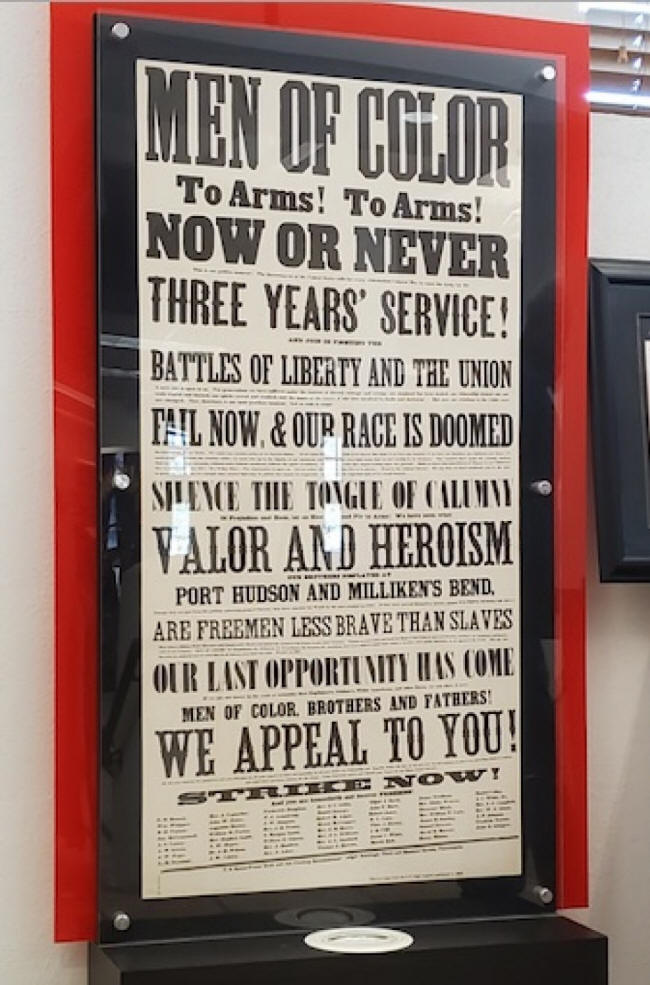

Army on Sept. 21, 1814 with the promise of equal pay. The Civil

War witnessed Union enlistment of approximately 200,000 African

Americans, an estimated 100,000 once enslaved, resulting in a

death toll of nearly 40,000.

The government enacted a law on June 28, 1866 that established

four segregated infantry and two cavalry

Buffalo Soldier units.

These regiments were created to “increase and fix the military

peace establishment of the United States”. They were stationed

in the South to enforce Reconstruction, build and repair

infrastructure and protect those engaged in the westward

migration. The Buffalo Soldiers enlisted for five years at a

rate of $13.00 a month and room and board.

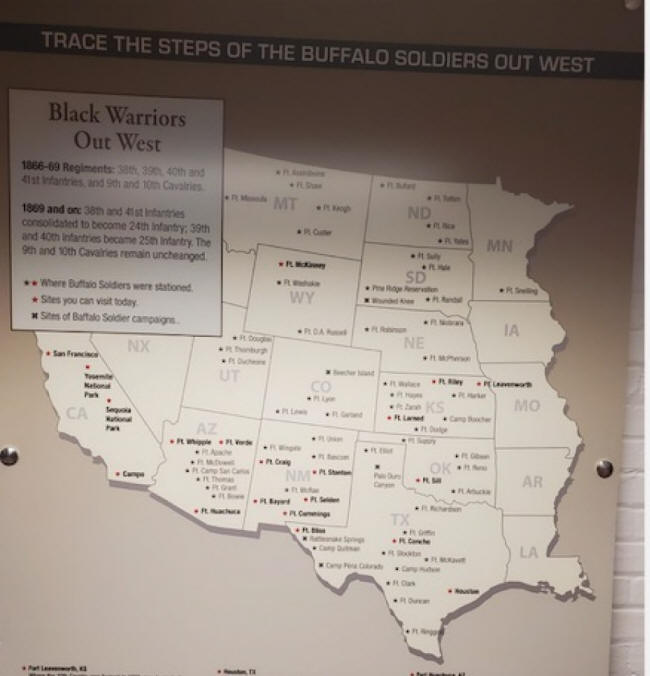

In the years they served they were stationed at nearly all of

the Texas frontier forts between the Rio Grande and the Red

River beginning with their first transfer to Texas in 1873. It

was they who erected forts, accompanied wagon trains, guarded

the railroads and mail, brought criminals to justice and fought

against Indian attacks. They accomplished all these things

while being issued substandard equipment and being victims of

unrelenting prejudice. Some white officers refused to lead

them, Custer being one of them, and they were restricted to

postings west of the Mississippi River because some whites

refused to have them in their area. In spite of hardships they

completed their jobs and served with honor.

The Buffalo Soldiers National Museum and The Center for African

American Military History are in Houston, Texas serves to

maintain and promulgate their history and legacy. It was

established in 2001 by Captain Paul Matthews and meticulously

showcases his astonishingly large private collection. Matthews

began his collection in the 1960s after learning of their

exploits. The 28 galleries are thematic and interpret the

history of the Buffalo Soldiers and the African American

military experience up to the present. An orientation movie is

offered before embarking on the self-guided tour.

Gallery 12 is the Westward Expansion. It is believed that the

Buffalo Soldiers received their name from the Plains Indians

because their hair and ferocity resembled that of the buffalo.

The name was a term of respect and the soldiers themselves

embraced it and incorporated the animal on their regimental

insignia. Former slave Lt. Henry Ossian Flipper’s story is told

here. In 1877 he was the first black West Point graduate and

served with the 10th Cavalry as the first black officer to

command in the regular US Army. He was targeted, court

martialed and dismissed in 1882. In 1999 he received a

presidential pardon.

Native Americans, Seminole Indian Scouts and the Indian Wars

introduces visitors to the Black Seminole scouts. The Seminoles

were asked to relocate to Texas, serve as scouts, and promised,

land, rations and pay. They served valiantly but the US kept

none of the promises even going so far as to stop rations for

their families. The unit was disbanded in 1914 and by that time

they had earned four Medals of Honor. The honorees are buried

in the Seminole Negro Indian Scout Cemetery near Fort Clark,

Texas.

President Theodore Roosevelt, after banding together a group

known as The Rough Riders, garnered a reputation as a military

tactician and leader during the Spanish American War. History

tells us that they charged Cuba’s San Juan Hill on July 1, 1898

but somehow omits, or downplays the fact, that all four of the

then existing regiments of the US Colored Troops also made the

charge. The Rough Riders and the 9th and 10th were the first to

charge. Gallery 14 returns them to the narrative.

William Cathay became a Buffalo Soldier on November 15, 1866.

Numerous illnesses resulted in visits to the post doctor and

the discovery that William Cathay was actually Cathay Williams,

the only woman to ever serve as a Buffalo Soldier. She was

honorably discharged. A short video and additional information

is located in Gallery 15.

The remaining galleries are filled with artifacts, art and

memorabilia on the World Wars, Vietnam, Persian Gulf, Pearl

Harbor, Women in the Military and the Camp Logan Race Riot. The

tour ends at the Medal of Honor Wall with information on the

nine Medal of Honor recipients.

Ultimately the Buffalo Soldiers were deactivated and integrated

into a racially integrated US Armed Forces as mandated in

Truman’s Executive Order 9981. The Twenty-fourth, the final

segregated unit, remained so until the Korean War in 1951.

One of the highlights of the museum is a Buffalo Soldier Mardi

Gras costume. It is located in the lobby and one should examine

the details closely.

This museum is a gem and not to be missed.

Note: Arlington National Cemetery’s Section 22 features a

Buffalo Soldier marker and memorial tree. The Rough Riders

Marker is nearby.