The Gardens and Grounds at Monticello

Story by Tom Straka

Photographs by Pat Straka

About a year ago we spent the better part of a day at

Monticello, the home of Thomas Jefferson. The details are in an

earlier article in this digital magazine. While Monticello

is recognized as one of America’s most famous homes, the

grounds surrounding Monticello are almost as interesting as the

house. They were attractive enough to bring us back for a

second visit, centered on the restored vegetable and flower

gardens, orchards, Jefferson’s favorite trees, and a bunch of

fascinating outbuildings. They were well worth a second better

part of a day. Tours at Monticello have various options, mainly

the house tour and the

gardens and grounds tour. The highlight of our earlier

house tour was Thomas Jefferson interpreter Bill Barker, who

gives a presentation as Thomas Jefferson and answer questions

afterwards. That presentation is out-of-doors and can be part

of the grounds tour.

Vegetable Garden

Thomas Jefferson’s vegetable garden was an essential part of

his plantation, providing fruits and vegetables as farm produce

to feed the large plantation population. While the garden was

fundamentally a functional enterprise, he included ornamental

features in the garden scheme. Jefferson was also a scientist

who managed the garden as a

scientific experiment. He kept a Garden Book which served

as his “research notes.” Part of the book was a “Garden

Kalendar” where he noted the dates of garden events (like which

plants could handle an early frost or the productivity of

various row widths). Just like his mansion, the visitor notices

all kinds of special features that make the gardens more than

long rows of plants. He experimented with plants from around

the world and even species like beans and salsify collected by

the

Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Due to erosion, parts of the garden were terraced in the

early 1800s, making this a sort of

garden plateau, hacked from the side of a hill by slave

labor and underpinned by a mammoth stone wall standing over 12

feet high at its highest. At the middle of the garden is a

garden pavilion, overlooking an orchard, vineyard, and

berry squares. Jefferson used the pavilion as a peaceful

retreat for reading in the evening. The garden provides a

awesome view of the undulating Piedmont landscape. The two-acre

garden is divided into 24 “squares,” or growing plots.

Jefferson divided these by which part of the vegetable was

being harvested (fruits, like tomatoes and beans; roots, like

beets and carrots; or leaves, like lettuce and cabbage). The

garden has many examples of

19th century vegetables and cultivation techniques.

The

vegetable garden today has been restored to its appearance

in Jefferson’s time, including his horticultural experiments,

plateau landscaping, and site for his 19th century vegetable

varieties. It does get modern maintenance, but 19th century

cultivation techniques are displayed where possible. Many of

the perennials are in the exact location specified by

Jefferson. The produce from the garden ends up in the

Monticello Farm

Table café.

A

level view of the vegetable garden, with Jefferson’s garden

pavilion in the background. Two acres is a huge garden; the

pavilion is at the middle, so a whole other part of the garden

extends beyond it. The pavilion has double-sash windows,

Chinese railing, and a pyramidal roof.

The view of the vegetable garden from above the

terrace provides a better perspective of the garden squares,

its massive size, and the huge diversity and variety of plants

that make it an edible laboratory. A sign at the garden notes,

“Jefferson’s garden was unusual, however, for its large size,

ambitious planting schemes, and strategic location that

promoted longer growing seasons.”

The plateau terrace and some

outbuildings also give a perspective of how the vegetable

garden is laid out. The garden is very long, with numerous

diversions at the top of the terrace to explore.

There

are all kinds of unusual plants to discover in the vegetable

garden. This is the

Hyacinth Bean arbor. The species is native to tropical

Africa. It was first planted at Monticello in 1804.

Mulberry Row

Just above the vegetable garden is Mulberry Row, the dynamic

manufacturing area of Jefferson’s 5,000 acre agricultural

operation. It is a long plantation street that served as the

center of work for dozens of craftsmen. It had more than 20

dwellings, workshops and storehouses. Today, it is mostly

foundations with signs explaining the crafts involved:

textile workshop,

joining and woodworking,

nailmaking,

tinsmithing, and

blacksmithing. There was also a

sawmill operation,

gristmill, canal operations, and a

charcoal burning operation to make fuel. The

charcoal sheds were on the west end of Mulberry Row. There

are many signs along the row describing the archaeological work

involved in locating building foundations and the artifacts

unearthed.

Mulberry

Row is a long plantation street above and parallel to the

vegetable garden (seen downhill in the photograph). It is

mostly foundations, but a few restored buildings are under the

mulberry trees.

The

Jointer’s Shop on Mulberry Row is typical of the

foundations along the street. The chimney and foundation are

all that remains. A joiner was a woodworker who made doors,

windows, and decorative finish work. Jefferson employed

highly-skilled joiners.

A

few restored buildings are on Mulberry Row, like the

forge and

quarters.

A

few restored buildings are on Mulberry Row, like the

forge and

quarters.

Isaac Granger Jefferson worked the forge in the original

building on this site, which housed a

"storehouse for iron" in 1796, a short-lived tinsmithing

operation, a small nail-making shop,

and also served as quarters for enslaved people.

Mulberry Row even has a

gravesite from a former owner following Jefferson’s death.

Monticello's Slavery History

The grounds include lots of interesting buildings.

Slavery is not hidden at Monticello and slave

housing is part of the outbuildings and is part of a special

tour. Most of the outbuildings supported the agricultural

enterprise, like the

stables. A plantation would need

ice in the summer and interesting structures like the

ice house can be found by wandering the

grounds.

One of four cabins that stood at

this spot that provided slave housing. During the colonial era

enslaved laborers lived together in large multi-family

dwellings; by the 1790s, many slaves, who pressed for

housing for their families, lived in single-family quarters.

Plantation Buildings

Eagle, Peacemaker,

Tecumseh, Bremo, Wellington, and Diomede were the six carriage

and saddle horses, plus one mule, who were stabled here in

1821.

The plantation had as many as 30 riding and carriage horses,

workhorses, and mules.

In the winter ice would be

harvested from the nearby Rivanna River and transported to the

icehouse

for storage. It took 62 wagon loads of ice to fill it. The cylinder

extends 16 feet underground

and six feet aboveground.

Flower Gardens

The

flower garden was next on our tour, but

was harder to find than the vegetable garden. While the

vegetable garden was highly organized and two-acres in size,

the flower garden is not in one place. It turned out to be

hiding in plain sight, along the roads and paths. It is a very

nontraditional flower garden, not a room outside, but an

exposed retreat. There are flowers bordering the West Lawn, for

example, and when you approach the mansion, the portico of

Monticello catches your eye and you tend to overlook the

flowers, looking at Monticello in awe. Once you look closer,

you realize the border of the West Lawn is a winding flower

garden.

The

West Lawn features the “Nickel View of

Monticello,” making it an icon of American landscapes. The

winding walk delineates the border of the West Lawn and that

border is one of the main flower gardens. Between the West Lawn

and the house are

more flower beds and one side of the

lawn has a

fish pond. Jefferson planned and

sketched the

winding flower border. He actually laid

the beds out in ten-foot sections, each compartment labeled and

planted with a different flower. The flower gardens are planted

as many as three times a year, early-, mid-, and late-summer.

There are also

fruit gardens: two orchards, two

small neighboring vineyards, and berry “squares.”

Along the winding flower beds,

with Monticello across the West Lawn. It is easy to see how the

building is a distraction from the flower beds, at least when

you first enter the West Lawn.

The winding border of the West

Lawn is a massive flower garden.

One example of flowers along the

winding border. Notice the hand-written label on the wooden

stake used to identify the plant. Some have “TJ” along with a

year written on top. That denotes a plant grown at Monticello

during Thomas Jefferson’s lifetime.

Not all the flowers are on

the winding border. These are at the front of Monticello.

Snow on the Mountain. A flower

on the winding path with a history.

You have to look at the hand-written label to figure out the

history.

Label for Snow on the Mountain. The code on

top of the wooden stake denotes this plant came from the Lewis

and Clark Expedition, with the year. The flower garden has lots

of interesting history hidden in it.

Trees

Trees were ranked at the top of

Jefferson’s hierarchical chart of favorite plants of

Monticello. Any tour of the grounds given by Jefferson would

include the highlight of his “pet trees.” He had 160 tree

species on the plantation. Native and exotic trees were planted

in groves. Ornamental trees grew near the house in “clumps.”

There were “allées” of mulberry and honey locust within his

road network and plantations of sugar maple and pecan. There

was even a living peach tree fence. Eighteen acres on the

northwestern side of the plantation were designated as the “grove,”

intended to be an ornamental forests with the underbrush

removed and the trees turned and thinned.

A

southern catalpa along the winding border, one of the

oldest trees at Monticello.

It was a favorite of Thomas

Jefferson.

Thomas Jefferson Grove today; as Jefferson

intended, it is almost parklike,

with a wide variety of unusual

ornamental trees.

Jefferson Family Cemetery

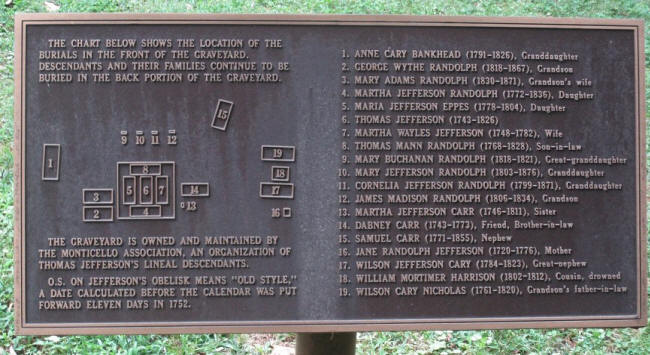

The Jefferson family cemetery is on the grounds,

downhill from the mansion. It is a stately cemetery.

Jefferson’s gravesite is visible from

outside the fenced exterior. Jefferson left explicit directions

on the shape of the obelisk that would mark his grave and the

inscription that was to be on the grave marker (and not a word

more). You usually have expectations of how something will

look; in the case of Thomas Jefferson’s gravesite the

expectation is ornate. In this case the expectation was met.

The obelisk which marks Thomas Jefferson’s

grave.

Thomas Jefferson’s gravestone obelisk

inscription, what he considered his greatest accomplishments.

The list of individuals that share this

cemetery with Thomas Jefferson is quite interesting.

Author/Photographer. Tom Straka is an emeritus

professor of forestry at Clemson University. He has an interest

in history, forestry and natural resources, natural history,

and the American West.

Pat Straka is a consulting forester and the photographer on

most of their travel articles. They reside in South Carolina,

but have also lived in Mississippi and Virginia.