|

|

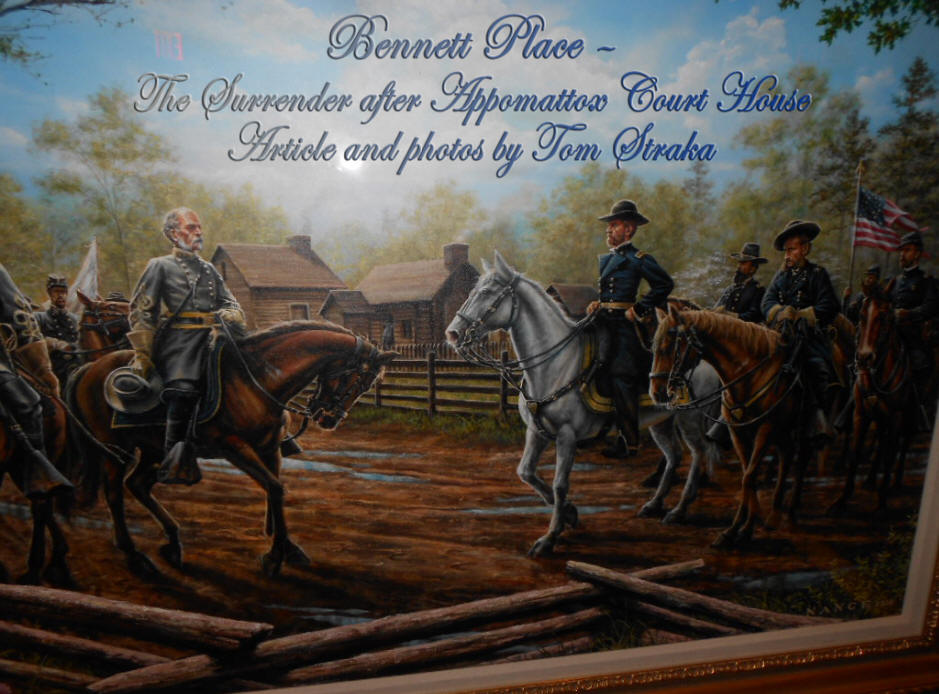

You

probably think the last surrender of the Civil War took place at

Appomattox Court House. Not so, there were several others as

Confederate troops further south and west surrendered.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis did not want the war to

end with Appomattox. By early-April 1865 it was apparent that

the Civil War was drawing to a close. General William T. Sherman

and his Union troops had finished their march to the sea and

were now marching through the Carolinas. Columbia, South

Carolina was burned in mid-February and in mid-March Sherman's

objective in North Carolina became clear; he was headed to

Goldboro to linkup with 30,000 additonal Union troops moving

west from the coast. Goldsboro

was important as it openned the door to Raleigh and the

important rail lines going north (the rail line that supplied

the besieged Army of Northern Virginia). Sherman hoped to move

north rapidly and join in the expected surrender of

General Robert E. Lee

and the Army of Northern Virginia.

|

|

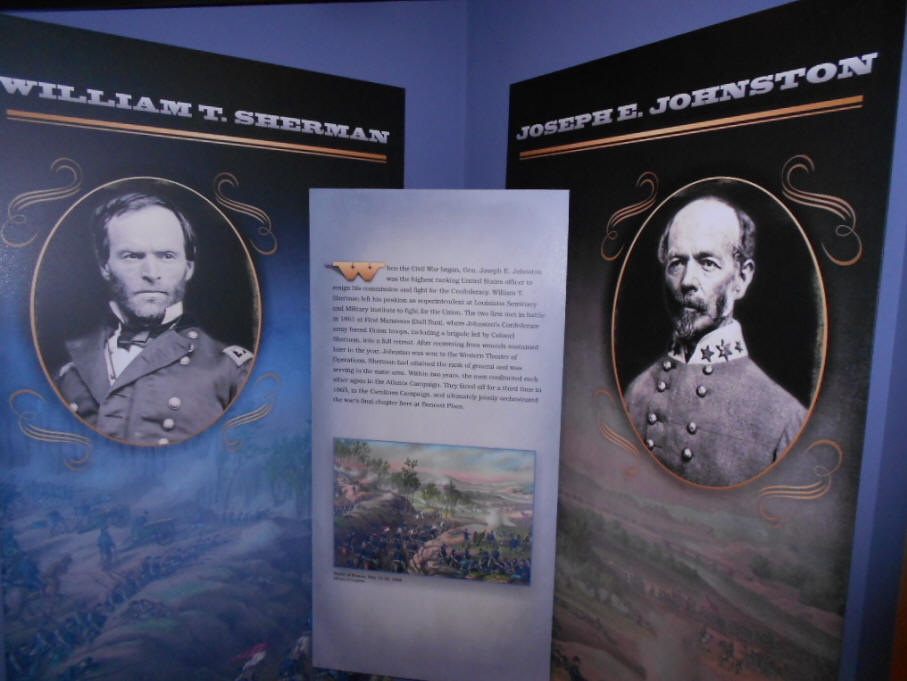

Two general who helped write the final chapter of

the American Civil War. |

General Joseph E. Johnston was in charge of the Confederate

effort to thwart Sherman.

The last major battle of the Civil War and the largest

ever fought in North Carolina would be at Bentonville where

Johnston attempted to ambush Sherman's troops. He failed to stop

Sherman and moved his troops east. In early April, Richmond and

Petersburg fell in Virginia and Sherman knew he had limited time

to finish his Carolinas Campaign if he were to participate in

Lee's surrender. But that surrender came quickly on April 9,

1865 and Sherman found out about it on April 11. President Davis

felt the war should go on. Finally convinnced by his cabinet

that a guerrilla war would just prolong inevitable results,

Davis agreed that General Johnston should contact General

Sherman and discuss peace terms.

|

Unity Monument, dedicated in 1923 as a symbol of

national unification. The two white columns

represent the Confederacy and the Union and are joined

at the top with a unity bridge. |

General Sherman had met with General Grant and President Lincoln

in early March to discuss possible surrender terms, so he was

prepared for surrender talks. Still, Sherman expected a final

battle for Raleigh. It never happened. Confederate troops and

the governor left Raleigh and on April 12 a group of promient

Raleigh citizens pleaded for Sherman to spare Raleigh from

destruction.

Sherman agreed and his troops entered the city on April 13.

Headquarters for the troops was the governor's mansion. The next

day Sherman received a message under a flag of truce requesting

a cesssation of hostilities so that civilian authories could

negotiate for peace. Sherman agreed to meet Johnston halfway

between their two locations, Hillsborough and Raleigh. That was

near a small station on the railroad line: Durham's Station

(current day Durham). Just as Sherman was leaving for Durham's

Station on April 17, he received word of Lincoln's

assassination. He did not want to imperil the peace talks, so he

swore the telegraph operator to secrecy.

The two generals met in an area of open fields and woodlands and

concluded they needed a building to meet in that would allow

privacy. Johnston had passed a cluster of houses, so the two,

accompanied by calvary, went there looking for a meeting place.

The first homeowner approached would not allow a Yankee in his

home, so they continued on to the farm of James Bennitt (later

spelled Bennett). The Bennitt family had lost two sons and a

son-in-law in the war. The family retreated to the nearby log

kitchen building to give the generals privacy.

Sherman described the

meeting as:

They met [flag bearers carrying flag of truce], and word was

passed back to us that General Johnston was near at hand, when

we rode forward and met General Johnston on horseback, riding

side by side with General Wade Hampston. We shook hands, and

introduced our respective attendants. I asked if there was a

place convenient where we could talk in private, and General

Johnston said he had passed a small farm-house a short distance

back. . . . We soon reached the house of a Mr. Bennitt,

dismounted, and left our horses with orderlies on the road. Our

officers, on foot, passed into the yard, and General Johnston

and I entered the small frame-house. We asked the farmer if we

could have use of his house for a few minutes, and he and his

wife withdrew into a smaller log-house, which stood close by.

General Sherman shared the secret telegraph with General

Johnston, changing the tone of discussions. Johnston felt that

Lincoln's death "was the greatest possible calamity ot the

South." Sherman offered Johnston the same terms that Grant had

offered Lee. However, Johnston felt their goal should be a

suspension of hostilities so that civilian authorities could

work out an end to the war. No decision was reached on the 17th

and both returned to their respective sides. A second meeting

occurred the next day at the same place. Johnston told Sherman

he felt he had authority to surrender all Confederate field

troops. Sherman offered terms similair to those offered by Lee

to Grant, but more generous. There was debate later on whether

those terms followed the plans outlined by Lincoln. When the

surrender terms arrived in Washington, Secretary of War Stanton

and Congress felt they were too generous. Washington rejected

them. Sherman and Johnston met again on April 26 and worked out

terms closer to what Grant had given Lee. Washington accepted

those terms.

Lee had surrendered the 28,000-man Army of Northern Virginia.

Johntson surrendered 90,000 troops in the Carolinas, Georgia,

and Florida. President Davis very much wanted the war to

continue, even as a guerrila action. He was not alone among

Confederates. Had the Bennett Place surrender not occurred,

Appomattox Court House could well not be where most Civil War

histories end.

Bennett Place Today

|

|

Museum display of items that might have been in the

farmhouse.

Drop-leaf table, Bennett family pitcher,

spool chairs, and portraits of Eliza and Lorenzo

Bennett.

|

After the war the site was spurned by North Carolinans, who were

not fond of the surrender. A new owner in 1919 had the idea of a

park, but the house, except for its stone chimmney,

burned to the ground in 1921.

|

|

|

| |

Confederate frock coat in museum. |

In 1923 a member of the North Carolina General Assembly obtained

an agreement to erect a Unity Monument on the site in exchange

for a 3 � acre grant. The monument was to mark national unity

(between Sherman and Johnston), as opposed to clebrating a

surrender. Prior the Civil War centennial, interest peaked in

Bennett Place.

|

| The museum includes weapons |

A condemened house that was very similair to the

Bennett hosue was moved to the site and restored, along with a

separate kitchen house, and smokehouse. Later, a visitors center

was constructed on the site, with an auditorium and museum. The

site is located within the city limits of Durham, very close to

Interstate 85.

Author:

Tom Straka is a forestry professor at Clemson University in

South Carolina. Photogrpahs by author.

American Roads and

Global Highways has so many great articles you may

want to

search it for you favorite places or new exciting destinations.

|

![]() Ads fund American Roads and Global Highways

so please consider them for your needed

purchases.

If you enjoy the articles we offer, donations

are always welcome.

Ads fund American Roads and Global Highways

so please consider them for your needed

purchases.

If you enjoy the articles we offer, donations

are always welcome.

--------

|