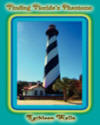

Cape Henry

Lighthouse's Unique Keeper

Cape Henry Lighthouse, the 4th oldest lighthouse in the United

States, was authorized by President George Washington in 1792.

In 1881, the government constructed a second lighthouse 350

feet from the first. You can visit but need to be cleared by

MPs first as they are on an active military base. A passport or

driver's license works.

You can climb to the

top of the

oldest lighthouse

but it's a stiff

climb. The

lighthouse was built

on a dune, so you

first climb a long

flight of stairs to

the top of the dune.

Then, it's 191 steps

on the steep spiral

staircase to the top

of the lighthouse.

Both lighthouses are

on the National

Register of Historic

Places.

The lighthouses are

a fun place to visit

but there is

something more in

their story.

Lighthouses are

beacons of hope, and

Cape Henry

Lighthouse offers a

story of one man's

hopes. From May 10

to July 26, 1870.

Willis Augustus

Hodges served as

the first African

American lighthouse

keeper at the Cape

Henry Lighthouse.

Hodges has an

interesting

background that

shows anyone

determined enough

can overcome

barriers. He was

born free in what is

now Virginia Beach

because his mother

was the daughter of

a white woman and a

black man. Hodges'

father had earned

his freedom by

working beyond his

regular duties on a

farm.

Being a prospering

free family didn't

make life easy for

Black people then.

They faced harsh

persecution in the

south, especially

after the Nat Turner

Rebellion in 1831.

His family moved

back and forth

between Virginia and

New York during his

youth.

Despite strong

anti-education laws

preventing Black

people from learning

to read or write,

Hodges received a

few months of

schooling and taught

himself to read and

write. As an adult,

he was nicknamed

“Specs,” for his

large, metal-framed

glasses. He was a

strong believer in

education and set up

a free school for

black children. He

advocated for

abolition, voting

rights, integration

of schools and

property rights. He

even founded his own

town, Blacksville,

in New York and used

his home there as a

stop on the

Underground

Railroad. He became

an ordained minister

and ran for office.

As part of his

campaigning and

educational push, he

created his own

newspaper, The Ram’s

Horn. During the

Civil War, he spied

for the Union.

In spite of the

harsh treatment, he

had received in

Virginia, he loved

his native state and

after the war he

returned there.

During

reconstruction, he

represented Princess

Anne County in

Richmond at the

Virginia

Constitutional

Convention.

An optimist to the

end, he wrote this

at end of his 1878

autobiography: “We

may not live to view

the promised land of

freedom and justice;

we may die in the

wilderness of

slavery and

injustice, just like

the older heads of

our children of

Israel, but our

children or

children’s children

will possess the

land, if God is God

and a just God.”

He died at 75 years

old on September 24,

1890 and is buried

in New York.